It was my second Gap Yah. I’d burnt through my first gap year’s savings, didn’t know what I wanted to do, and had all the time in the world to try out YOLO but feel FOMO seeing all my mates graduate while I stagnated in an existential skidmark of my own making.

Sorta.

It could be pretty dope just mopin’ and copin’. I worked many jobs, some happy, some crappy, but did them all coz the tax man cometh regardleth if you hath purpoth or noth. I sold raffle tickets to old dears, climbed structurally unsound ladders in structurally unsound warehouses, took chisels to the face (admittedly, by my own hand), all to stave off the tyranny of rent and anomic drifting inherent to the seemingly infinite expansion of my initial gap year. This drifting was variously benign and benighted: its zenith being creative procrastination, its nadir straight nihilistic misanthropy. I sturmed und dranged till a mate told me to get with a labour hire company to at once become a real man of the people (not the tryhard inner-west fauxletariat my aborted first year of Arts trained me to be), and entrust the admin for the material sustenance of my existence to a benevolent (and unionised) agency that would surely uphold my best interests in its employment of me.

I went to some drab office in Burwood, signed a thick insurance waiver, and I left with naught but a naughty wink from the boomer receptionist on the way out.

Their first assignment for me was in Bondi. Sick. Beaches, babes and Bondi Rescue. I’d be working on some beachfront McMansion and end every workday with some shirtless dips in the poser outdoor gym, followed by some more shirtless dips in the ocean, then go home and enjoy the sweet sleep of the labourer. Then my boss texted me that I had to get there at five am, requiring me to wake up at four am. Yuck. Ah well.

After a sackwhack of an alarm at four am, I chugged some toilet paper coloured porridge, slapped some Kmart-tier tradie gear on my back, then braved the train to Bondi Junction with the rest of the hi-vis four am mob. Not the liveliest of mobs. Veterans slept the whole journey and had this outré knack of waking up just before their stop, though noobs had to settle for a well-timed alarm, often blaring J Biebz or Tay Tay to shatter at once the collective REM cycle of the quiet carriage as well as the macho veneer of their tradiehood.

From the Junction I caught some passengerless ghost bus up the hill towards a lighthouse-looking thing near my worksite. On the way out it was hard to tell if the driver’s eyes were open behind his speed dealers.

I got off at my stop. The bus roared off in a black fart of exhaust incongruous with the austere beauty of Sydney before sunrise surrounding me and the far-flung hilltop on which I now stood. The hilltop was charmingly clad with recently mown grass and a crown of sandstone boulders on its seaside aspect. I scanned around the wintry Bondi morning: the lighthouse-obelisk-thing on the escarpment to my right, a gaggle of small brick huts surrounded by cyclone fence to my left. Where was the worksite?

There. A tradie ambling over to the edge of the escarpment, his arms reaching out to the vast dark sea spanning eternity on the horizon. The sun came and the man clutched out at it like a drowning sailor snatching at a lifering. The sun’s fingers sprent from the horizon out over us then over the city behind, where the moon still sat, all fat and blue, presiding over the last moments of its reign. I whipped out my phone to etch the near syzygy of the giant orbs onto my tiny screen. The tiny screen doesn’t quite do justice to the scale ay; nor does its pixel density quite capture the deep drenching gold of the sunrise now bleaching the beach back down the hill.

As old mate’s continual clawing at the sun went from curious to concerning, an engine’s grunt and the scrunch of gravel alerted me to my boss’s arrival. His polished Redbacks are first out of the Merc, then his legs – hairy javelins – leading up to well-worn ball-hugger stubbies, an RM Williams flanny and an unzipped Northface puffer, finishing with his craggy lips sipping from his bespoke ceramic keep cup.

‘Ah you found the worksite mate, hardest job done’.

I nodded with unconvincing empathy as he related to me in gruff avuncular platitudes about how there’s nothing-like-a-hard-day’s-work-with-your-hands you-know-what-I-mean but those fat-cats-in-the-big-end-of-town-wouldn’t-know-about-that-ay sorta thing before clapping me on the back and handing me a hard hat from the back of his Merc.

‘Where is the worksite?’ So said a South African accent from behind me speaking exactly what I was thinking.

Blessing Mbabwe stood there in identical Kmart-tier tradie gear to me except with glasses thiccer than old oatmeal and a black chromedome balder and shinier than a magic 8 ball.

Turns out Blessing was another labourer from the company who had been told where to go, got there, but didn’t know what there was. We exchanged pleasantries and our boss handed him a hard hat and ushered us towards the brick huts on the other side of the road. It was hard to understand how this small and ugly enclosure could command such royal real estate in this cashed-up postcode – and what was that beige obelisk thing on the escarpment?

‘Is that a lighthouse back there above the cliffs? – and what is Sydney Water?’ asked Blessing, again speaking for both of us as we walked through the gap in the fence and saw a small laminated sign bearing the Sydney Water logo. Before our boss could answer a voice called out from inside the closest hut:

‘Come on in boys!’

A beer-bellied bogan called Bob beckoned us into the building. The wall to my right was empty bar a window framing the now sun-soaked Bondi. Looking left there was a table bearing a papier-mâché scale diorama of the exact same scene of the beach seen through the window, even down to the tiny Irish backpackers getting sunburnt near the shore, and a large screen and projector with some chairs half-heartedly plonked around it.

‘Looks good doesn’t it’ said Bob, pointing at the diorama.

Blessing, distinctly unimpressed, said ‘Yes, I suppose it does look good. But please, sir, could you tell us where we are working today?

Bob pointed underneath the table. The diorama had an underground section. A perfect scale model of a lift going down to the floor, where the model opened up into a flurry of cross-sectioned tubes spiderwebbing around a large brown mass fitted with long rectangle pools, each filled with poo-brown cellophane.

‘Welcome to the Bondi Sewage Treatment Plant mate’

Blessing’s mouth opened and would not close.

‘Well get you down there soon enough, but we gotta give you your induction first.’

He clicked his clicker and the Cold War era projector on the wall hummed and sputtered then spat out a picture of a degloved hand.

‘Just a bitta O haitch ‘n S to get you sorted’.

Our boss took his cue to drop a weighty clap on our backs and a mouthed ‘She’ll be right’ before slinking into a serpentine grin and then out the door with his plumber’s crack winking at us just below his North Face puffer. We could hear him whistling ‘Working Class Man’ as he climbed into his Merc then fanged far away off into the day.

After watching some more body parts whose skin was in various states of undress, Bob summarised his presentation with an earthy ‘Don’t be [redacting] stupid and you’ll be right’.

Blessing looked at me, still agawp, a bead of sweat rolling from his forehead onto the rim of his meaty prescription goggles.

Bob took us to a low-slung brick hut with a few picnic tables scattered around it and a board sporting a single-digit scorecard for ‘Days Since Last Accident’ written in foreboding red. At this point, Blessing and I felt reassured our labour-hire company knew they couldn’t have told us what the job was before contracting us to do it.

A man walked out of the building and his face caught up a bit later.

‘Ah what’s this who are youse, oh Bob where are you goi- oh you’re the new labourers, well get over here we’re all coming out in a moment, I’m the foreman by the way, ok stay here and listen to Mick, I forgot to get me coffee.’

And off he went back into the building.

The building looked too small for the simply enormous men that came out of it. The clown-car exit was led by a man that must’ve been Mick because he looked like a Mick and said ‘G’day I’m Mick’ in a gravelly contrabasso that was pushed painfully past the subbasement of his vocal folds to remind you that not only was Mick a man, he was more a man than you and beyond a reasonable doubt more hard than you. The men behind looked like the most lumpen of proles you could chuck a hammer and sickle at: there was Shazza, who looked like a slightly decomposed Shannon Noll; Dazza, who had proven true the ‘Most likely to end up in jail’ award he won in high school; and the squat and mesomorphic Nugget, who looked like a leathery hobbit that had been left too long in the deep frier. The rest of the crew were either swole (est. avg. weight 110kg) hardmen bedecked in tatts and Lynx Africa or girthy apprentices with receding chins and cascading mullets tucked into their collars. They slumped onto the picnic tables that bowed under the weight and we all faced the door.

With a roar, the foreman emerged from the building. Now caffeinated, his face was in tune with the rest of his body and his mouth had found its operating frequency: loud and lewd. Amid the flurry of words illegal and immoral that Blessing would never unhear came a message along the lines of ‘new day but same shit, don’t do anything [redacting] stupid or you’ll die and legal will breathe [redacting] brimstone down my [redacting] neck.’ Once he was done, Mick grunted and our platoon got up in sync and headed towards another nondescript building off to the side.

‘Not you’ he said pointing at Blessing. ‘You’re with them’ he said pointing at another gang of gargantuan grunts. Blessing looked at me, wide-eyed, his forehead shiny and slick, then disappeared in a melange of stained orange vests and jumpsuits.

We piled into the new building to face the lift we’d seen from the diorama. It was the only thing at the end of a long sterile corridor that was all lye on the lino floor and all tallow on the sallow walls. I looked at the lift and felt amiss. It seemed to grow closer yet remain the same size, vertiginously zooming towards us with a depth of field that would’ve curdled Kubrick’s milk. We marched to it like soldiers about to go over the top: I noticed gnarled faces next to me soften, eyes leaving bodies as stares lengthened past the lift now a thousand yards away, hands grabbing themselves with the compulsions of a recidivist alcoholic.

We arrived. The doors opened and I was slapped in the sinus by the worst smell I’d ever smelt. The others didn’t seem to notice and shuffled in without complaint, faces rehardened. The two colossi I was smooshed between probably didn’t notice the five-foot-eight munchkin about to dry wretch into their elbows.

The last thing I saw before the lift doors guillotined shut were the watery whites of Blessing’s eyes, tearing up at the smell and the shipwreck that his Monday had now become.

***

The trip down was long. I found not-breathing preferable to breathing through my mouth as the smell of the lift had a taste that scorched the tongue. The lift just kept going. Please Lord, may it stop. As my last active synapses were trying to work out the length of the descent based on hasty estimations from the scale of that godforsaken diorama, the lift stopped.

The doors opened and my nostrils flared in agony. This was now the worst smell I will ever smell because the searing sulphur that had just cauterised my nose’s insides ensured I’d never be able to smell properly again.

Some poor reprobate had scratched a jagged ‘Welcome to Hell’ in the sandstone wall opposite the lift, likely the last thing he ever did before he was dragged to the lake of unquenchable stench just next to the lift. I’d never smelt so much poo in one place and was getting entranced by its grotesque siren-song aroma before the echoing scream of the power-tools knifed through my eardrums, permanently circumcising the top octave of my hearing range.

I stumbled out of the lift.

While I was whizzing through the various stages of grief at the loss of my senses, Mick and his grim and grimy lieutenants marched me through the tunnels to our worksite. On a walkway I looked down and shouldn’t have. We were suspended over a cesspool three times the volume of an Olympic diving pool, the sewage dully reflecting the dim and dour fluoro globes overhead.

‘Pretty much the shit comes in from there’ Mick pointed to an enormous pipe to our right – ‘we put our shit on it here’ – he pointed underneath us – ‘then it gets shat out to sea over there’ – he pointed through a door marked “to outfall pipes” – ‘fall in here and you will die.’

I noted the barricades stopping us from falling into the cesspool underneath were at triphazard height. As we kept on down the tunnels the prospect of sun and sand and shirtless dips every workday petered out like the sputtering death of a wet fart.

‘This is us.’

The path opened up into an enormous chamber lit by yellow safety lights at thirty metre intervals.

‘We’ve cleared out this plenum – he pointed up – ‘and are gonna put in a new air con unit. Now we need to bash the old metal off the walls’ – both arms pointing out like a crucifix to remind me in which direction walls were meant to be – ‘and add them to the pile’ – he motioned at the ziggurat in the centre of the room- ‘then sort the good from the bad and then we’ll take it outside’.

I scarce can take it in.

‘Ok. How will the metal fit in the lift?’

‘Don’t be a smartarse. Did you see the diorama? Follow Hamish, he’ll tell you what to do.’

A two metre labrador with a dopey smile bounded over.

‘Hey mate what’s your name? He asked boganly.

‘I’m Br-

‘Yeah noice to meet ya I’m Hamish. Mick told me you’re new and you’re helping me. Our job is to sort the good metal from the bad metal’

‘Ah right. What’s good metal?’

‘Stuff you can recycle’

‘How do you know good from bad?

‘Good looks like this’ he picked up some metal from the periphery of the ziggurat.

‘Bad looks like this’ he picked up a different, but identical-looking piece of metal.

‘Right.’

‘Then we put it on a trolley and push it from here to the other side of the plant where there’s a gate where a small lorry will be waiting for us. We pile it in and come back and do the same thing till it’s done.’

‘I see. How long have you been doing this?’

‘Yeah ummm, I’ve bin ‘ere loike a year and bit, should be another two to go. Haha hope I’m done before my eighteenth, don’t know what I’ll be like if I can get on the cans before work’.

Oh. Hamish is young but looks old.

‘You’re an apprentice?’

‘Haha yeeeah boi. Pay’s shit; work’s good but.’

The work was not good. It seemed a competition to produce the loudest and ugliest noise possible by the loudest and ugliest men possible. We bashed the walls with hammers while the apprentices would take turns holding bits of metal up to their goggles while the other cut through it with the shrill caterwauling of the buzzsaw, sparks flashing up the whites of their eyes, their smiles death-hilarious. For some reason, Shazza, a CrossFit fiend who hit up the doof every weekend and turned up to work every Monday half-putrefied with involuntarily jerking lips, had uncontested control of the aux and a sizeable amp he’d proudly named the ‘tradio’. Much to the ire of everyone in earshot, his music taste consisted solely of death metal covers of top 40 schlock, turnt up past eleven, the bassy booms of the tradio literally shaking the metallic Jenga underneath it.

So there I was, sorting the wheat from the chaff, metal recyclable from the non, all so the workers here would have better air con. Future workers that is. Obviously we didn’t have any air con, so you could just feel the heat of the stench enter your pores when sweat wasn’t pouring out of them. In truth the odour of the plant was a smell more felt than smelt, and it felt like depression.

My eyes started to glaze over as the fog from my breath misted out my goggles and everything started to vibrate. Ghosts from farts of Christmases past steamed up from the cesspools and eddying phantasmagorical vapours slunk from the walls, coalescing then firming into misty shapes in front of me. The vapours and fart-ghosts eventually settled into a dreamlike cloud representation of my childhood Shetland sheepdog, Spud, who sniffed the tradio with mordant curiosity then raised his leg and marked himself on it, before decomposing back into the phantasmagoric fog. The absence of my earplugs, somehow lost on the lift ride down, left my eardrums getting mincemeated and engraved by the apprentice’s manic hoots and gibbers, the guttural death metal screams of ‘BABY BABY BABY OHHH’ and the incessant wailing of the powersaws. The violence of the noise caromed off my synapses, percussively concussing me from the inside and threatened to rob me of my inner life forever when I saw another dark shape materialise in front of me: eldritch, dripping, ominous. It started to speak to me, a lispy whisper at first:

‘Psshgfssm’

A mess of sibilance.

‘Pisg fsarm.’

Somehow the whisper was hearable amid the surrounding cacophony.

‘Pig farm.’

Then it crescendoed.

‘Pig farm. Pig farm! PIG FARM!’

I blinked and the dark shape became Blessing, his contorted lips inches from my face, yelling ‘THIS PLACE IS A PIG FARM! A PIG FA-’

‘Oi!’ One grunt from Mick was enough to cut through my stupor, vanquish the apprentices’ horseplay and leave Blessing with sudden onset aphasia. He pointed at Hamish, me, the trolley. No grunts required. I mouthed a quick goodbye to Blessing as his eyes rolled backwards into his head and I skedaddled away with Hamish.

We hauled the metal and our arses up a long winder of a path, curved and carved through the grungy Sydney sandstone. The path was sporadically lit by halogens trailing cords that spagetthied for miles down the walls of the cave. After an hour of asking Hamish the odd question to distract from the encroaching darkness and keep his V8 motormouth fueled on topics I could understand, we arrived at the gates of Hades themselves. In the darkness, they opened. The promised lorry rolled in then rolled out with our metal, leaving us the long and lonely walk back with the empty trolley.

After another hour we got back to the ranch.

Even with Mick onsite, the apprentices seemed destined to choose the dumbest, most dangerous and least efficient way of doing things, though in an agreeably schaudenfreude kind of way, sort of like watching babies or drunks on the verge of a nasty fall. Just as I was hearing the call of the void to join in with their exuberant idiocy, Mick barked something at a subordinate who barked at his subordinate to get some tools with me from the storehouse – this chain of command leaving me with zero doubt as to my exact place and worth in the worksite powergame.

Dazza, a man who looked like he knew all the best spots to hide a body in your local state forest, came up behind me and whispered ‘Follow me’.

We headed into deep darkness past the end of the main hall we’d been working in. The halogens got sparser and sparser as we wended through the maze of tunnels. We reached a fork: lights to the left, abyssal darkness to the right.

‘I wanna show you something mate.’

He hooked sharply towards the darker side. I followed him until I heard a noise. I thought I heard the pitter patter of small steps, neat of foot, behind me. Nothing. I kept on round the bend. Dazza was nowhere to be seen.

‘This way mate, almost there’ I heard him whisper, almost cooing, from the obsidian mist ahead.

The pitter patter returned. I whipped around. There back at the fork entrance I saw those deep black Disney eyes pouring out their Machiavellian payload into my mirror neurons. It was Spud, the darling sheltie of my youth. He hissed at me, paused, then slunk off, his Prince Charming tail unfurling like a banner round the corner till he was gone. Why am I seeing these things? Underfoot I felt grooves: scratches that seemed like the clawmarks of a ravening beast. My mind started to trace words into the grooves – what, where, why, help, scream. After walking blind for too long I realised I hadn’t heard Dazza in a while. I cast back to when I saw him behind Mick in the hall, the way he fawningly pawed and fingered his sledgehammer, his Vlad the Impaler eyes dancing with intensity above his teardrop prison tatts.

Perhaps I should’ve made a will before working here.

‘Ah, um, hey Dazza, we close to the tools yet?’.

Silence.

I heard a wrenching sound from the deep.

‘We’ll hit up the tools soon enough mate.’

And then he opened it.

Honeyed light came from on high. Golden Sydney sun just lathered the hallway, seemingly evaporating the grime that ensconced us, throwing the scars and lines on Dazza’s face into sharpest relief. We looked out at the roiling surf, the beautiful breakers, that true Australian blue in sky and sea. We stepped out onto the rocks. Behind us the sandstone cliffs snaked away beyond sight in bands of gold, pink and white. We just stood there. For ages. Something moist appeared on Dazza’s face, melding into the teardrop tatts that dripped down his cheek into his ‘Only God can judge me’ neckline graffito. He pointed out a rusty pipe opening to our left.

‘Y’know, this used to be where the effluent pipe connected to the plant. Back in the day we use to pump our shit just out there’ – his fat fingers pointing about 300 metres out from Bondi beach – ‘so surfies used to warn the grommets to watch out for it: the infamous Bondi cigar. Floating logs, you know. BS I reckon. Our poos are liquified into effluence; it’s all one big churned up stream of our mess. Maybe you’d get some tampons and condoms that’d survive primary treatment, but I dunno about full blown cigars. Anyway, point is we spewed it out the front of our most famous waves for decades till they built an underground pipe that releases it with Nemo and Dory a few ks out seaward.’

Dazza looked like he was going to keep talking but caught himself and stopped. He put down his hand and looked directly into the sun. In silence we left.

***

‘Smoko!’

Above the din and sin of the worksite Mick’s contrabasso rang out like a thunderclap. Tools were dropped and we hustled for the lift. A grinning Hamish punched one of the other apprentices when Mick had his back to us. We clambered into the lift, endured the neverending ride back up, and were greeted by the foreman, somehow more blearyeyed than before. ‘Wash your hands unless you wanna die, there’s a thousand [redacting] bacteria down that chute that’ll crucify your insides’.

After peeling off gloves, helmet, mask, earplugs (if remaining) we washed ourselves in this long trough along the wall outside. The lumbering cadre of workers became assiduous Lady Macbeths, scrubbing their arms from cuticle to weenus til their skin looked raw.

Smoko doubled as lunch, coz the powers that be determined it was more efficient not to take two lift trips back up during the day. We went into the mess hall and retrieved our lunches from our bags at the back of the hall.

Mick had four frozen meat pies and (naturally) had first go of the microwave.

Shazza had a protein shake and a quinoa salad. ‘Game Changers mate. Don’t want cloudy blood to spoil this temple’ he said while proudly pointing at his rig. And what a roided-up Zyzz-rig he had (needed some work on the zygomatics though).

Shazza was a rig; Mick was a rig; Hamish was both a rig and an absolute unit. Nugget was a rig too, but at five-foot nothing could not qualify as a big rig.

Nugget had his reading glasses on, the AFR open on his knee and reheated McNuggets (no kidding) on his lap.

The apprentices were showing each their insta feed, which mainly comprised vids of other apprentices being stupid, Bondi influencers pushing the limits of how much skin they could show without getting their account terminated, and gambling ads designed to corrode the soul and savings account. Two apprentices were enjoying a back and forth about said influencers:

‘Haha reckon these Bondi chicks know about us bro’

‘Bro don’t be [redacting] stupid how would they know us bro’

‘Nah bro I mean about us, underneath Bondi, that there’s a literal lake of shit underneath them?’

‘Brah they don’t even know that the botox underneath their lips is toxic, how would they [redacten] know what’s under their feet.’

‘Tru bro truuu’.

Hamish sat down opposite me and plonked a reusable Woolies bag on the table. As Hamish started manhandling the food out of the bag and tipping it into his mouth, excess spilling onto the bench, it became clear why he was an absolute unit. He had two boxes of Teevees, two packets of Tim Tams, two packets of chips, and a six pack of V. No one batted an eyelid as Hamish sunk his lunch in a clearly ritualised order of food then drink (packet then can, box then can and so on).

‘Is this your lunch every day Hamish?’ I asked with genuine concern for his diabetes risk.

‘Haha yeah bro. I buy it at the servo on the way to work.’

‘How do you get here?’

‘Mick picks me up at like quarter to four in the morning, then we go get Shazza, hit up the servo then get here just on five’

‘Whoa what? – that’s so early. Where do you live?

‘Blacktown brah. Yeah how good’s my lunch but’.

I didn’t know what to say so I looked around the array of rigs in front of me to see if anyone shared my concern for the nutritional value of Hamish’s feed.

‘Nah its shithouse,’ said Mick.

Hamish just laughed his kookaburra cackle and continued sustaining his absolute unit status by wolfing down his monthly kilojoule maximum in two and a half minutes.

‘Runt’ll be dead by thirty’ said Nugget, without looking up from the stocks and the races on his lap.

Blessing popped his sweaty head round the corner.

‘Where can I buy lunch from around here?’ he asked with a slight tremor.

Mick just pointed up the road.

All the hauling arse I’d done with Hamish meant I’d demolished my sandwich and was still hungry, and Blessing looked in need of a chat (and a hug) so I went with him to the tuckshop down the road.

‘Bruddah, I must tell you something in all sincerity and in all seriousness: our boss is a lying prick. I ran an IT empire back in Cape Town and now I’m shovelling shit in this pig farm because of his filthy pig farmer lies. I want to go home – I have a PhD in Computer Science and now all I can smell is bloody methane.’

‘Yeah mate it sucks.’

We both looked down over Bondi from the small knoll next to the tuckshop. Some lifesavers dove into the surf after some tourists who had misjudged the rips. Insta boyfriends drearily made their girlfriends objects of public consumption. Gulls circled overhead and around our feet, waiting for Blessing to drop his chips.

‘We’ve been set up bruddah. We’ve been set up. I want to go back to South Africa.’

I looked up at God’s handiwork in the clouds as Blessing kept reciting, half to himself, ‘We’ve been set up’, while he rocked back and forth, hands on knees. The gulls seized their moment and his chips, but Blessing was gone, long gone, and didn’t notice.

‘We’ve been set up, we’ve been set up, we’ve been set up…’

***

Blessing never returned to hell. He was a man of his word (unlike our pig farmer boss) and apparently (according to our pig farmer boss) caught a flight with his family back to Cape Town the next day. Why he ever left his IT empire for the Bondi Sewage Treatment Plant I’ll never know.

My return to the plant the next day was painful. It’s harder to wake up early when you know you’re doing it to get to the lift to hell on time. I got up and geared up. The train ride seemed glummer than yesterday: a Vietnamese brickie sat with bowed head as he punched himself arrhythmically in the glutes to keep himself awake and a Maori scaffolder gave advice to his Lebanese builder mate about how to keep his Brazilian lollypop lady sidegirl after she started seeing another Lebanese builder from a rival company.

From the station I took the same bus with the same bus driver. Again, I couldn’t tell what was going on behind the speed dealers. Again, he dropped me off as dawn was cracking on the bumcrack of Bondi. Again, there was old mate, the heliotropic zombie, trying to grab the sun with a kind of haphazard determination. Some matching, blue-rinsed, lycra ladies with their toy poodles in matching knitted turtlenecks gave him a wide berth as they wobbled past on their morning gossip. Eventually he just stopped and sat next to the big phallic lighthouse thing, looking at the heritage-listed Indigenous carvings at his feet.

The foreman appeared over the rise of the hill a lumbering, slobbering, somnambulant mess. I could hear him say strange words under his breath.

‘Anh. Cryptosporidium. Colloidal. Jenny. Anh. Gantt chart due Monday. Anh. Duong.’

He bumped into the fence and had a spasmodic shudder before coming to and successfully navigating the gap in the fence.

The rest of the tradies dripped and drabbed in but the Blacktown boys all arrived at five am sharp. Mick marched towards me out of the carpark. ‘You’re here. The boys reckoned you wouldn’t come back. Usually youse labourers piss off quick after the first day down the lift.’

No mention of Blessing not being here. Ah well.

‘Hey Mick, just a quick one, is the foreman ok? He looked a tad cooked this morning.’

‘Was he sleepwalkin again? Yeah poor bastard lives in Katoomba. Fair trek for him every morning. Well most mornings. He sometimes, ah, stays in town if it’s too much for ‘im.’

‘Who’s Anh? Jenny? Duong?’

‘Best not to ask champ.’

Back down the lift, the smell was somehow just as bad, despite my nostrils being cauterised from the day before. Hamish and I were on wheat and chaff duty again while Shazza was tasked with banging the wall, something he did with aplomb and in time with the hardcore cover of Ariana Grande’s Bang Bang blaring from his tradio. To anyone with the misfortune of being nearby he’d shout, ‘I just love hitting shit with hammers. Great for my aesthetics too. Chicks [redacting] dig my rig.’ Meanwhile, Dazza hung around dark corners as the apprentices were testing how close they could get their eyes to buzzsaw sparks without going blind.

Halfway up the winding path for another metal delivery, Hamish remembered another path that could cut our trip in half. We got to a steepish slope and could hear the gates of hell opening and closing over the rise. Hamish had enough forethought to know we would need a running start, but not enough forethought to know what to do if our momentum ceased and the 300 kilos of janky flint-sharp cargo threatened to turn our faces into a colander.

Our push stopped about twenty metres from the lip of the slope and the jenga tower of death bobbled and groaned in our direction. I slammed my inconsiderable bulk against the trolley to prop the back wheels while Hamish held the top while on his tippytoes.

‘[Redacted].’

Before we could think of what to do some tradies on a small golf-buggy type thing whizzed by and saw our predicament. Without stopping they said ‘[redacting] apprentices’, laughed, and sped over the rise of the hill.

‘So sorry mate, I did this last week and forgot it didn’t work. We’ll have to go back’ said a sheepish Hamish.

We managed to roll it back slowly, at the meagre cost of our pride and Hamish’s lower back. Once we’d delivered the trolley the low and slow way, we were shuffling back down the path to the corner near our pit when something pink flashed before our eyes.

‘What was that?’ Hamish seemed ill at ease.

We rounded the corner.

‘Is that – a woman?’

In truth, I’d forgotten women at work was a thing after a day and a half working down the lift. And there she was in pink hi-vis, flanked by Bob and the foreman who were eagerly pointing at things for her to tick off on the list on her clipboard. She looked like Alice who after being promised Wonderland instead saw Nugget scratching his arse with a hammer first thing out of the rabbit hole and was therefore distressed and confused.

***

As the bus took me past the beach to the train station, I couldn’t help but prefer to work literally anywhere else. I looked out over Bondi. The cerulean waves nurdled lazily into shore as some Colombians taught some Germans how to play foot volleyball on the sand without much success. A frisbee floated high and white in the sky like an oblate seagull, holding in the air perfect and still as a three-quarter moon, before boomeranging back to shore with swift and final purpose. On those long Bondi stairs women talked to women about other women while burnished men envied each other’s physiques on the way to the outdoor gym. Some kids enjoyed themselves, other kids eyed off unattended valuables on the beach.

Surely I can work somewhere above ground, if not outside; how about that picture framing place in Marrickville, I could learn to stretch canvasses with my housemate. Musings led to memories, chiaroscuro and half-suppressed, dancing in and out of me; the days sans work, those days when I wouldn’t, couldn’t, leave my room, bar those trips to the toilet where my neon-brown piss would burn me, before I’d go back to my floor to inflate my sleeping bag with milky farts, look at my laptop for fourteen hours and slip back into the Numb, the anodyne of unsatisfying sleep. The worst work was better than that. Surely. The sun winked out of sight as I hustled underground to catch my train back home.

***

At smoko the next day Mick saw fit to (again) act out the hijinks from his infamous gap year in Bali.

‘Boys, I was doin the thousand pushups a day challenge. I started doin fifty reps at a time but couldn’t keep it up. Eventually I was just like sets of one hahaha like “one, one, one” but lost count. Anyway me and the missus would be blind as on the beach and these monkey looking blokes’ – here Mick pursed his lips and held his arms out like an orangutang with invisible lats syndrome – ‘kept bringing us these cocktails that were pretty much just rubbing alcohol and guava. Or just straight arak. Anyway, we spent our savings in 2 weeks on that good shit. Good to do this stuff before having kids.’ There were some chuckles and murmurs of assent rippling through the boys though at least one of the Asian tradies present had raised an eyebrow during the orangutang display. The chat rolled into the perils of domesticity and women in general; crude would be too kind a descriptor for how they described women. Chat died when the bell signalling the end of smoko rang. Faces hardened, ‘she’ll be right’ was collectively thought and mouthed, then back down the lift we went.

***

The final push. We were meant to be all on hand to get the wheat and chaff sorted, but Mick was off somewhere else more important, so the higher ups told us we had to pull our [redacting] socks up to get enough scrap for the double lorries they’d booked to be worth it.

The site was a mess. In their appreciable lack of judgement the apprentices had decided now was a good time to change over all the rusty discs in the buzzsaws and throw them at each other like ninja stars. In a hypnotic, dancelike, fervour of sweat and hammers, Shazza and Dazza were doing well hitting things off walls but not doing well in sorting things on floors. Hamish was hangry, Nugget was nowhere.

I was disassociating. The cumulative effect of this stultifying steampunk daymare was to abrade my qualia and thereby rapidly shrink the experiential map of my lifeworld: my eyes were blinder, my ears deafer and my heart harder, impelling me to escape by overlaying images of comfort onto the desecration of my surrounds. Spud featured chiefly, my dearest darling dog wandering around, sniffing the gear and wagging his tail and pantaloons at me in encouragement. Lord get me out of here.

When our hellscape had gone full Bosch in that Spud was nowhere to be seen and the apprentices started to look like the flying monkeys from the Wizard of Oz, I heard a rushing of wind from the far corridor. We all looked up; hammers and discs halted mid-air, the tradio silenced and Nugget popped his head up like a prairie dog from under the ziggurat.

Mick had returned.

‘What the truck are you runts doing’

He pointed, he yelled, and his word worked powerfully in us sorry sods until we moved with the coruscating harmony of a Rolex’s inner parts, the jewel movements of a Rube Goldberg. Mick was like the bogan at the caravan park who becomes Einstein when faced with an engine, us now his tools as he entered flow state with a succession of pointed fingers, f-bombs and c-nukes. The trolleys were loaded, the lorries were filled and the boys were geed up. Mick may never read Rousseau, Rowling, or even the Very Hungry Caterpillar, but boy could he lead a worksite.

We’d done it, but I was done with it.

The bumpats, broad horseshoe laughs, and loud ‘how goods’ echoing off the walls of the lift up weren’t enough to dissuade my conviction that this would be my final dip into the stinky Styx. Even the most enthusiastic of swoletariat camaraderie felt like not enough polish scraped over too much turd, and what an enervating turd this gig had been; my soyboy sensitivities could not cope with the working man’s lot any longer, particularly not at twenty-three bucks an hour. As we left the lift, I left the boys in the hand washing line to text my housemate I’d take that warehouse job in Marrickville.

***

Shazza, Dazza, Nugget, Hamish and our pet apprentices were sitting on the picnic tables waiting for Mick to finish talking to the foreman inside the hut.

‘How often does Mick do that?’ I asked.

‘You mean when he goes super saiyan? Hahaha whenever we need it’ said Hamish with characteristic relish.

‘Runt’s been leading worksites since he was fourteen. His dad was the same.’ said Nugget with uncharacteristic approval.

‘Yeah Mick’s sick. A sick[redacted] too coz he gives us lifts’ said Shazza.

Dazza just stared into the sun, still looking for Zihuatanejo, while the apprentices perved on their phones.

‘What’s that lighthouse thing on the escarpment by the way?’ I asked.

Nugget’s face crinkled slightly more than it already was. ‘You mean the thing that looks a giant grey [redacted]? That’s the poo pipe mate. Farts out gas so we don’t get gassed down below.’

Before I could trouble Nugget with more questions, Mick reemerged. ‘Well done boys. Foreman pleased with the double lorries getting done. Also – he pointed at me – happy to keep you on for next week.’

‘Noice! And good stuff Brod. You work hard even though you don’t know anything useful lol’ said Hamish.

Some murmured agreement from the table.

I suppose there was no better time to inform them I wouldn’t be coming Monday.

‘Aw [redacted] me dead. At least you tried mate. You labourer soft[redacteds] usually only last a day.’ said Nugget

‘Thanks Nugget.’

‘Yeah bro you tried.’

‘Thanks Hamish’.

‘Now I have to hire another [redacting] labourer. Thanks mate. Don’t forget to submit your timesheet and truck off.’

‘Thanks Mick’.

Shazza gave me a twitchy nod and Dazza briefly looked down from the sun, grunted at me, then looked back up. The apprentices didn’t notice. I said goodbye and packed my things and left. I saw the foreman talking to himself through the hut’s window. I waved but his eyes were glassy and didn’t see me as I made for the hill.

Getting the working man’s approval for three hard days’ work gave this soft inner-westie bohemian a spring in his step on the way down to the beach.

Didn’t even wanna bus it.

I threw my clothes off into the shore and lay on the sand euphoric, just in my undies. As the day hit golden hour Bondi hit full majesty, and, aside from the odd backpacker or truant, there weren’t many to appreciate it, or ruin it. I tried to imagine what it was like before the white man filled it with his crap and his crappy jobs.

The chiaroscuro images returned, friezelike, careening in and out of my euphoria to the tune of the Soviet national anthem as pristine, cigarless water lapped my cast-off filthy clothes. I saw the workers. Their lips pursed in some gross chauvinism: slurring women as mere flesh for their flesh, not of their flesh; even as their sweat slicked off the mothers and daughters inked on their arms, chests, faces; even as they repeated ‘she’ll be right’, not as a mere hard-yakkaish, bruxist mantra, but as an exhortation to keep existing as real and needed as fresh daylight. Their hands, deformed haptically and septically by their work, swinging hammers in synchronous union; the foreman’s face riven with acne scars, dermatitis and worry. Nugget’s catarrhal whines, Mick’s racism, Blessing’s cursing. Dazza murmuring to himself about shit blokes like himself that put up with the shit that no one else does to keep our shit safe and away from our beaches. Men from everywhere converging on nowhere to be seen and thanked by no one.

What is working class man, that thou art mindful of him?

I paused my thoughts mid-chorus and thanked God my housemate had told me they needed more hands at the art warehouse in Marrickville. I gave the poo pipe, the giant cigar, a final wave before heading for Bondi Junction station.

***

Sydney train rides to or from the east are uniquely conducive to navelgazing. It started to rain lightly on the way past Edgecliff into Central, giving my wistful stare out the window the emotional heft and sonder of late high school angst. Manual labour away from home was so much better than gap year acedia in my home, in my head; it puts off the pixies that forewarn depression – those pixies that dance on my frontal lobe with steel wool on their feet, that tread and shred my consciousness into static like a psychic winepress.

Surely no job of mine could ever be as bad as what I’ve just done – everything will be ecstasy in comparison.

***

As I got off at Marrickville it was dark outside but my heart was light. As I walked to my front door I knew the job was done, I wasn’t going back, all was well.

I crossed the doorframe, then I felt it.

I may have left the Bondi Sewage Treatment Plant, but it had not left me. My certainties collapsed on themselves, all that was solid became porous and boy did my head hurt and my stomach blurt and what is happening to me I must get to my bed I must stop this aching must stop this feeling what is this feeling I must disrobe I must disrobe stop panicking stop stop panicking just slow down it’s nothing it’s not something, but what is this moiling roiling inside of me that is me oh it’s going it’s going ok is it gone? It’s gone. Let’s stop.

Somehow I made it upstairs to my room, my pants hanging round my steel-caps, my head through the armhole of my sloppy joe. Just a bit of nausea. She’ll be right.

Be still mate.

Be still.

I’m still.

And then I chundered everywhere.

Like a Chinese firecracker I thundered out both ends, seeing this morning’s pork roll flash before my eyes through my legs into a violently brown Pollock on Duchamp: my splattered toilet bowl. I lost three kilos in two days, dry-wretching like Gollum between my legs as I jettisoned pure Fiji water out my bum. The call of shame followed.

‘Mum’ I croaked out like a cane toad with emphysema.

‘Son! How’s uni going? Oh that’s right, I forgot, you’ve taken your “year off to write”. How’s that going for you now that you’re on your second “gap year”, you know the point is it’s just a one year gap right, that’s why it’s called a “gap” – I hope you haven’t gone through all your savin-

‘Mum how do you get poo out of sheets?’

‘-What? What!? Are you okay!? Who pooed in your bed?’

‘I did Mum, I have no control at the moment. There’s poo everywhere. Help me.’

‘Ahh! Um, um, just spray some Napisan on it!’

‘Mum, I’m a young single man, I don’t own Napisan.’

‘Well just make a paste out of washing powder and spread it on the stain- wait what happened? Are you ok?’

‘Bondi happened.’

I chundered my last, all over the phone, hearing Mum shriek through the vom-covered phone speakers as I lay back defeated, arms outstretched in my own skidmarks and chunklets.

I’ve never vomited since.

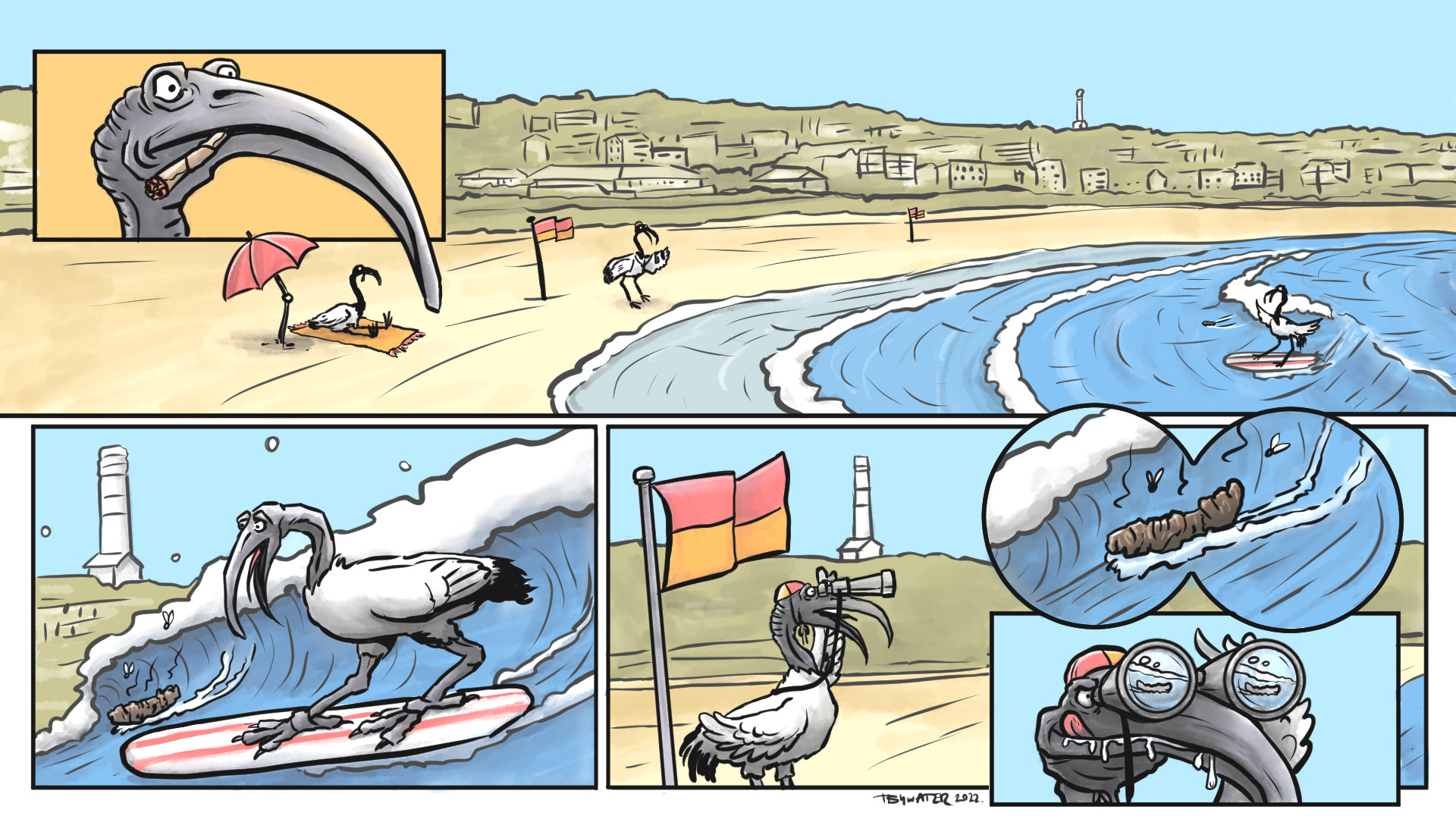

- Art by Tim Bywater at timbywater.com

- Check it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKFjWR7X5dU

3 responses to “Scarred by the Bondi Cigar”

Congrats Brodie! And awesome artwork Tim 🙂

Over a year has passed since you sent this to me and, only now have I finally gotten around to reading it. Oh dear lord in heaven! Is this based on a real lived experience? If so, you have my deepest condolences. That being said, despite the dirty work that is often remarked as ‘having to be done by someone’, I no doubt believe that you have been excreted out of the other end of this said experience, with a deeper appreciation for the innerworkings of our day-to-day existence.

Your piece of writing was so extremely vivid with its descriptions, that I felt as if my mind was being flayed with every sentence I deciphered hahah. It was almost painful having to confront those Australian-tradie stereotypes head-on, the language they all (we assume) use and their ‘she’ll be right’ work ethic. Coupled with your absurd verbosity and ceaseless discharge of cultural-references to media, history and other such mediums, made for a roller-coaster of a read, both enthralling and anxiety inducing. The only glaring criticism I would give this piece of work is perhaps its uneasy flow from sentence to sentence — very much akin to having too much chili or grog, sometimes the lines flowed as gracefully as burning diarrhoea does on a Friday night pub-crawl session with da boys (using your poo story to inject some shit symbolism of my own 🙂 ). I gave you the benefit of the doubt because it is very much in line with the very nature and tone of the story being told and the characters within it.

Despite not having shared directly similar experiences myself, it all seemed very viscerally familiar — it felt uniquely Australian (as I am sure the intent of the piece was). I haven’t really known or been able to explain what culture Australia has compared to other nations or places, but here I felt as if I had known about it my whole life yet never really acknowledged it. This story has left an indelible mark on me, such as the smell of a turd lingers with you long after you have wiped it from your shoe and showered it in Glen20 or OUST (3 in 1).

[…] like my Bondi experience […]